Arctic Marine Tourism

PAME has worked on the topic of tourism in the Arctic and continues to do so. First, PAME published the Arctic Marine Tourism Project in 2013, following recommendation from the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (2009) report. The result was the AMTP Best Practice Guidelines which were followed up with a workshop and an analysis of ship traffic, published in 2021.

Current work

PAME continues to follow ship traffic closely and is developing an Arctic Shipping Status Report on the topic. Furthermore, Canada and the UK are co-leading the Arctic Marine Tourism: Mapping Whale Watching in the Arctic project. The project will compile the first information on whale watching tourism in the Arctic using PAME’s ASTD in conjunction with industry engagement and a review of online information, in order to better understand recent development of this sector and to identify gaps in the data. Longer-term, this work could help inform the development of responsible marine wildlife watching measures.

While vessel-based tourism has the potential to affect whales, responsible tourism can also make a substantial contribution to local Arctic economies and whale conservation, through data collection, citizen science, and raising awareness. It is therefore important that this industry develop in a sustainable and well-managed manner, guided by research and the best available data.

The project will compile information on whale watching tourism for the Arctic using PAME’s ASTD Program, in conjunction with industry engagement and a review of online information, to better understand this sector and identify gaps in data through:

- Updating analyses previously carried out on Arctic marine tourism including the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and PAME’s report on Arctic Marine Tourism and conducting analysis of trends in Arctic marine tourism based on information from the ASTD Program, and potentially other complementary datasets, with respect to the number of cruise ships, their size, and whether they offer whale watching excursions as part of their itinerary;

- Identifying Arctic ports and harbors where whale watching operations take place and compiling an inventory of operators and their fleets; and,

- Identifying data/information gaps and potential ways to address these, for example, which vessels are broadcasting AIS A, B, or not at all, and how often these vessels encounter whales.

PAME's Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (2009) spoke extensively on marine -based tourism in the Arctic. In recognition of the wide-ranging management challenges associated with the growth of tourism in the region, PAME initiated a follow-up project in 2013 attempted to identify issues or gaps where the Arctic Council could add value and culminated in the creation of a range of voluntary best practice guidelines encouraging action by the Arctic Council, Arctic States, or collaboration between the two.

PAME's Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (2009) spoke extensively on marine -based tourism in the Arctic. In recognition of the wide-ranging management challenges associated with the growth of tourism in the region, PAME initiated a follow-up project in 2013 attempted to identify issues or gaps where the Arctic Council could add value and culminated in the creation of a range of voluntary best practice guidelines encouraging action by the Arctic Council, Arctic States, or collaboration between the two.

The result were the 2015 Arctic Marine Tourism: Best Practice Guidelines, a voluntary document encouraging action on behalf of the Arctic Council, Arctic States, and in some instances collaboration between the two, and is meant to strengthen, not preclude, the range of existing mandatory requirements and voluntary policies and guidance currently in place to support sustainable Arctic marine tourism issued by levels of government, industry, industry associations and the NGO community.

The 2015 Guidelines included several recommendation, of which PAME followed up with in a new project in 2019; The Arctic Marine Tourism Project: Passenger Vessel Trends in the Arctic Region (2013-2019) (AMTP 2021).

The project comprised of two work packages:

- Work Package 1 (WP1): Compilation and analysis of data on tourism vessels in the Arctic using PAME's Arctic Ship Traffic Database (ASTD) to better understand recent developments.

- Work Package 2 (WP2): Summary of existing site-specific guidelines for near-shore and coastal areas of the Arctic visited by passengers of marine tourism vessels and pleasure craft

The project report includes the analysis, made by the British Antarctic Survey and further analysed by the PAME Secretariat, graphics, maps and other information, also available below in the project repository.

The report also includes a standardized template that could be used for the development of site-specific guidelines aimed at tourists/vessel operators, and tailored towards, inter alia, mitigating safety and environmental risks, encouraging sustainable use, and educating visitors on ecological, cultural, and historical features unique to particular areas. An explanation of the methodology used and the step-by-step approach to be employed is also included. This was done in close collaboration with the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO).

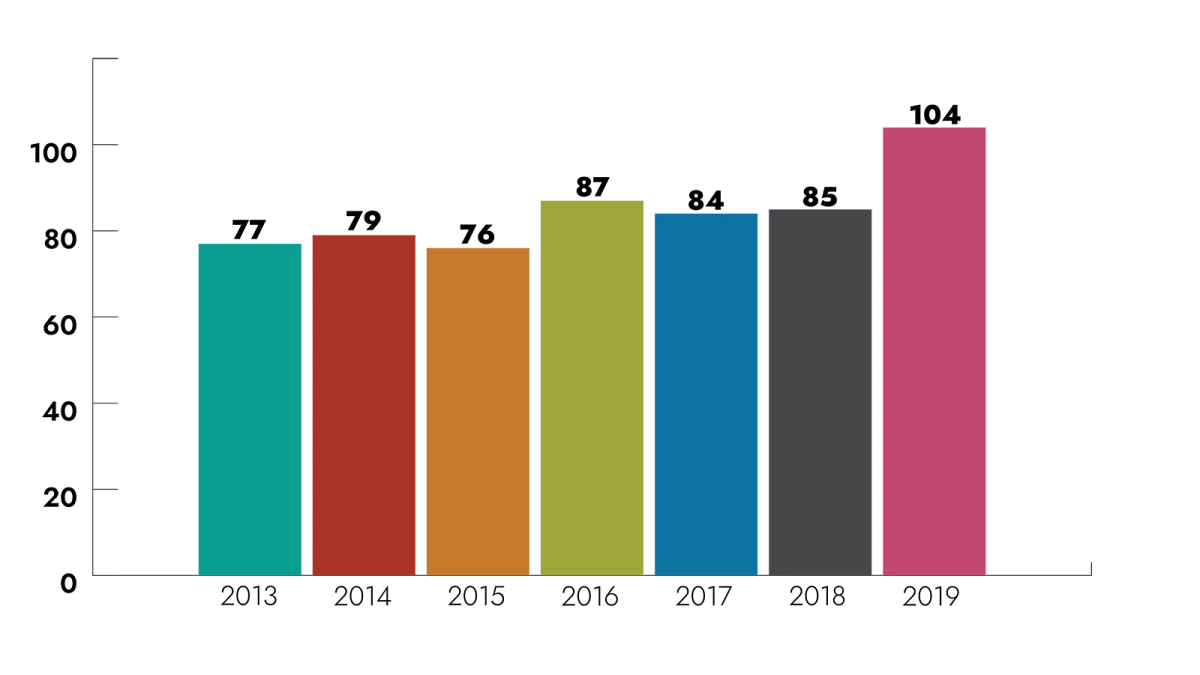

There are multiple ways to frame levels of ship activity within a given geographic area. One common methodology is to tabulate the number of unique or individual ships operating within a specific area - referred to as unique ship count. This method counts each ship only once, regardless of whether there are multiple entries and exits within a preset polygon. From 2013-2019 there has been a gradual increase in the number of individual passenger vessels operating within the Arctic as defined by the Polar Code. The total increase from 2013 to 2019 is 35%.

2021 Tourism Project Workshop

2021 Tourism Project Workshop

In 2020, the project co-leads convened a face to face workshop to advance the project.

Presentations:

- ASTD: Tourism vessels in the Arctic (Hjalti Hreinsson - PAME Secretariat)

- Marine Domain Awareness - Arctic Canada (Dominique Jolicoeur - Transport Canada)

- AECO Cruise Database (Troels Jacobsen)

- AECO's Site Specific Guidelines (Edda Falk)

- Cruise tourism in Iceland (Elías Bj. Gíslason - Icelandic Tourist Board)

2015: Arctic Marine Tourism Project (AMTP)

From 2013-2015, PAME developed the 2015 predecessor of the 2021 report.

PAME organized workshops to identify issues or gaps where the Arctic Council can add value by articulating best practices in relation to vessel-based Arctic tourism.

The result of this project is a best practices document that:

- avoids duplication by being aware of existing guidelines and best practices

- identifies existing best practices while also determining any practical problem areas or actual issues requiring some resolution

- takes into account regional variations, categories of tourist/vessel operations, various stakeholder perspectives, and practical us ability of a best practices document; and

- considers the intended audience(s) for development of best practices.

The final report was released in 2015 and introduced at the Arctic Council ministerial meeting in April.

The final report was released in 2015 and introduced at the Arctic Council ministerial meeting in April.

In the context of the AMTP ‘Arctic marine tourism’ is understood to include activities or interactions that are in some way facilitated by (though not limited to) the operation of a vessel in Arctic waters. While a convenient shorthand, it is recognized that the term does simplify an otherwise diverse industry and range of activities that reflect many regional and geographical variations.

Accordingly, unless otherwise specified, the best practice guidelines that follow are intended for broad application and not necessarily exclusive to vessel operators, but rather the coastal administrations and local communities directly involved in aspects of Arctic marine tourism as well. ‘Sustainable Arctic tourism’ is given the same definition used by the Arctic Council’s Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG) in the Sustainable Model for Arctic Regional Tourism (SMART) Report to mean “tourism that minimizes negative impacts and maximizes socio-cultural, environmental and economic benefits for residents of the Arctic”.

The AMTP best practice guidelines is a voluntary document encouraging action on behalf of the Arctic Council, Arctic States, and in some instances collaboration between the two, and is meant to strengthen, not preclude, the range of existing mandatory requirements and voluntary policies and guidance currently in place to support sustainable Arctic marine tourism issued by levels of government, industry, industry associations and the NGO community.

Click here to download the report.

The project gratefully acknowledges funding from the Nordic Council of Ministers.

History of Arctic Marine Tourism from the AMSA Report

For most of European and American history, the many attempts to explore and occupy high latitudes were characterized by peril and tragedy. From 1576 onwards, numerous ventures into these cold, remote and icy places were conducted to obtain economic benefits and expand empires. All of the expeditions experienced hardships and many ships foundered and men perished in their attempts to penetrate these unknown seas and lands. By the 1800s, newspaper and book publications describing both the heroic and tragic aspects of polar exploits were immensely popular. Given these widely publicized descriptions of a bleak Arctic environment and the fatal demise of Arctic expeditions, it is remarkable that such a place would be attractive to tourists.

But, in fact, tourists began visiting the Arctic in the early 1800s and their attraction to this unlikely destination has grown steadily for more than two centuries. Arctic Tourism for the Masses By the mid-1850s, the Industrial Revolution was far more than an economic phenomenon; it had transformed societies by creating personal wealth for greater numbers of people, increasing leisure time and improving public education. It introduced new technologies, especially transportation and communication, which facilitated convenient access to the remote parts of the world. One result of these transformations was the extraordinary expansion of tourism. The combination of widely distributed personal wealth, the invention of railroads and steamships with enormous passenger capacities and progressively affordable transport costs suddenly allowed thousands of people to travel for pleasure. By the late 1800s, tourism had become a viable leisure activity for the masses, rather than the indulgence of a privileged few.

By the late 1800s, steamship and railroad companies had achieved the capacity to transport large numbers of passengers. Given intense competition between those companies, travel costs were progressively lowered to attract customers and successfully compete. Simultaneously, companies aggressively expanded their transport networks to previously inaccessible regions, including the Arctic. All of those business decisions enabled more people to travel to more destinations. In 1850, Arctic marine tourism by commercial steamship was initiated in Norway. By the 1880s, Arctic marine tourism was a booming business. Arctic destinations included Norway’s fjords and North Cape, transits to Spitsbergen, Alaska’s Glacier Bay and the gold rush sites as far north as Homer, riverboat cruises in the Canadian Yukon, and cruises to Greenland, Baffin Bay and Iceland. The tourist experience aboard the steamships was a mixture of exploration and luxury. Little known or recently discovered glaciers, bays, wildlife and indigenous communities attracted curious tourists led by Arctic explorers and naturalists. Shipboard life emphasized lavish meals, concerts provided by orchestras, beauty parlors and barbershops, photography studios and lectures presented within library settings.

All of the 19th century Arctic destinations were commercially successful and cruise ship companies have continued to operate and expand their itineraries throughout those and other Arctic regions for more than a century. In addition, the combined themes of expedition and luxury cruising have also persisted to the present time. By 1900, Arctic tourism was a flourishing commercial activity. Its diversity included independent travelers pursuing a variety of adventurous recreation activities in marine and land environments, as well as groups touring natural, wildlife, historical and cultural attractions. All of these Arctic tourism activities were extensively promoted in guidebooks and the popular press.

Companies specializing in guidebooks, such as John Murray and Baedeker, came into existence at this time. And travel literature encouraging mass travel regularly appeared in widely distributed periodicals such as Harper’s Weekly, The Century Magazine and the National Geographic Society Magazine. From the mid-1800s onward numerous editions of Arctic guidebooks would regale the splendors of the Land of the Midnight Sun. The economic benefits of the Arctic tourism industry were immediately evident to both private companies and Arctic governments. Tourism provided jobs, personal income, revenues and financial capital for infrastructure. It also represented a new way to use the Arctic’s natural resources. It was a departure from the resource extraction and depletion industries such as hydraulic mining, rampant timber harvesting, and the exploitive commercial fishing and whaling practices of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Arctic Council Working Group

Arctic Council Working Group